An Evening with J. D. Salinger

Why did his elegance surprise me?

In the winter of 1952, I received a telephone call from my mother, Jane Canfield. There was to be an evening party at my parents’ house on Thirty-eighth Street, she told me. “A Harper’s party,” she added, Harper’s being the publishing house of which Cass, my step-father, was chairman. My mother said that I would be a welcome guest and that my younger sister, Jill, and her husband, Joe Fox, were expected.

I had graduated in June the previous year, delayed by two years in the Navy, at the end of World War II, and another year as a student in France. I wanted to be a writer. The Harvard Advocate had published a short story of mine. In Archibald MacLeish’s writing workshop I had started to write a hopeless novel, and had continued to its uninteresting conclusion months after graduating. Now I was a marketing trainee with the Texas company Texaco and would be posted to West Africa in the summer. These were my last months in New York.

My mother continued, “Someone that I know you admire has accepted—J. D. Salinger.”

I told her I would most certainly come.

The Catcher in the Rye had come out the year before. I had read it with enthusiasm but not with the extreme admiration I felt for his short stories in The New Yorker. They seemed to me matchless in their vividness, especially in conveying his characters’ subtle and complex emotions.

When I arrived that evening, Mary, the maid, was waiting at the door to take the guests’ overcoats, and I could see that the house was as finely turned out as it could be: flowers in the vases and the antique furniture shining. “The bar is on the porch,” Mary told me.

I got a drink and joined Jane and Cass in the living room with “Mac” MacGregor, Harper’s editor-in-chief. Soon Jill and Joe arrived, and for a short time it was a mostly family party. Then, nearly all at once, the thirtysome others crowded in, Salinger among them.

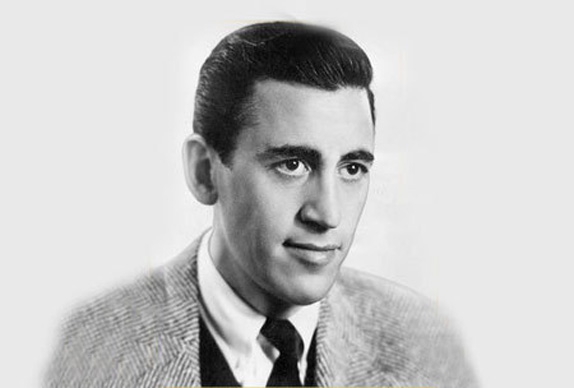

A headshot of him had appeared on the Catcher book jacket—dark hair slicked back above a longish, handsome face. This night he was well dressed in a suit with a faint glen plaid pattern, a white shirt whose collar was secured behind the knot of his necktie by a gold collar pin. His cufflinks caught the light. Why did his elegance surprise me?

I felt some shyness shaking all the hands, particularly Salinger’s, and felt certain that Jill would, too. Joe was never shy. He was the one who told Salinger that it was a pleasure to meet him and how much he admired his work.

Joe had been the captain of the Harvard swimming team. He had majored in English, but I’d been surprised when he declared that he wanted to work in publishing. He was a book salesman for Alfred Knopf at the time of this party, but he later became a well-known, much respected editor at Random House, working with such writers as Truman Capote, Philip Roth, and Martin Cruz Smith.

Salinger shook all hands with apparent ease. I had the feeling, however, having been looked squarely in the eye by him and having watched him shake the hands of Jill and Joe in the same manner, that he was glad to see some relatively young guests. He was thirty-three that year.

Dinner was eaten from my parents’ best plates balanced on the guests’ knees. Wine glasses were filled and refilled. Book gossip was exchanged. Conversational companions changed often with the changing of dishes and drinks. For a considerable time Jill and Joe and Salinger and I were all sitting on the living room’s carpet. He asked us to call him Jerry, then asked some routine questions about what we were doing and why, but with a pleasing sympathetic intensity. He made several comments that put him on our side, the side of people starting out rather than the people settled in to lifelong careers. The conversation warmed, and we found that we could make each other laugh.

He seemed especially interested that Jill was a painter and that our grandparents, our father’s parents, had both been painters who had lived in Cornish, New Hampshire. Salinger told us that he knew Cornish. I told Jerry that I had written a novel that no one would ever publish and got a complicit nod for which I was grateful. Our small group became increasingly hilarious and was eventually broken up by Jimmy Hamilton, who wanted Salinger to meet someone he thought important.

Toward the end of the night, as the other guests were putting on their coats, Joe found me in the front hallway. He spoke into my ear, “Jerry has asked us up to his place for a drink. Are you game?”

We three had our coats on, waiting for Salinger to say his good-byes, then he joined us and we went out to the street and found a cab immediately.

What a great turn of events! For Salinger to be taking such interest in us!

In the apartment, which was a brownstown further uptown, Salinger asked us what we would like to drink. I offered my help getting out the ice, but no, he’d prefer to do it himself. The bar’s bottles and glasses were arranged at one end of a counter between the small kitchen space and the living room, and we stood around while Salinger poured—whiskey for all, I think. Drinks in hand, Jill, Joe, and I sank into a long sofa across from the bar, Jill sitting between us. Salinger sat down on a chair facing us across a coffee table.

In my buzzy contentment I looked around the room at the pictures on the walls, and I lost track of what Joe and Salinger were saying to one another until I heard Joe ask, “Where did you go to college, J. D.?”

Salinger did not immediately reply and in that momentary silence the mood in the room changed. I caught my breath. I believe that Joe’s businesslike tone could be heard as faintly aggressive; it was familiar to my ear.

Salinger said evenly, “A little college in upstate New York. A college you’ve probably never heard of.”

“Which one?” Joe asked. Nothing suggested that Joe had heard anything in Salinger’s voice but information sharing.

After another short silence Salinger said, “Hamilton. Does it make a difference to you, knowing that the name of the college is Hamilton?”

“Where is Hamilton?” Joe asked. Did he need to know Hamilton’s location? I dreaded what might follow.

“I suppose you both went to one of the Ivies,” Salinger said. “Maybe you both belonged to the same club. Perhaps at Harvard?”

Joe and I had in fact belonged to the same club at Harvard.

But now Salinger began talking of something else; I didn’t immediately grasp his subject. Buddhism, his studies in that religion, and his wish to go further in those studies. He said, “I’d be surprised if any of you think of yourselves as Buddhists.”

He talked about the discipline of meditation, of what might be reached through its practice, of a book that had helped him to appreciate its benefits. Of “levels,” or did he say, “stages of enlightenment.” He spoke more quickly as he went along. Perhaps it was simply impatience with our ignorance. I was not keeping all the information straight.

He said something about his own achievement level of Siddhartha. “I’d say that you,” he pointed at Joe, then at me, ”are at” and he mentioned a low level. He said he would put Jill at a higher level.

Some sound or subtle movement on Jill’s part made me glance at her. Her face was shiny with tears. She did not move at all or make any sound, but when I looked up both Joe and Salinger were staring silently at Jill.

Joe stood up. He stooped over Jill saying something that got no answer, then said to the room that we would have to go now.

“Yes,” I got to my feet. “We really have to go.”

Joe and I fetched our coats and Jill’s while she and Salinger stood silently. As we headed for the door Salinger came alive and spoke up. “No, no,” he said. “Please don’t go. Please stay and have another drink. Don’t go now.” He was shaking his head.

“Really, we must go,” I said. “I’m sorry.” And I was, I certainly was.

I did not understand exactly why Jill had broken down, but it was impossible to think that we could stay.

We stood awkwardly on the sidewalk waiting for a cab. One came quickly and Salinger asked again that we change our minds. “Come back in, please, have another drink.”

The three of us got into the cab. Joe gave the driver my address and when the cab began to move Salinger began walking, then running, alongside, still asking us to change our minds. He hit the cab—with his fist, I supposed—and the driver braked.

Joe said, “Drive on!” Salinger was looking in through the window beside me. “Stop. Please come back!” He was shouting now in the quiet street.

The cab moved and got through the intersection. Joe said angrily, “He’s absolutely crazy.”

I do not remember anything else being said during the short ride to where I was living. Jill and Joe kept the cab and went home.

During the days and weeks that followed I brooded about what had gone wrong with the evening. I wanted badly to understand it. Something critical had been said or done. What was it?

SEVERAL YEARS after the party, I learned from Jill that at mid-evening she had gone up to our mother’s bedroom to use the bathroom and that when she came out of it she had found Salinger lying on the guests’ coats piled on the bed. He had proposed to her that she leave the party with him right then, that very minute. He would drive them to Cornish that night. They would leave everything in their lives and start a new one together.

I asked her why she had said no.

“I was smitten with Jerry that evening,” she admitted. Then she added, “But I wondered what he and I would be saying to one another around Hartford”—Hartford being about halfway to Cornish.

I’ve often wondered if Jill has ever thought of contacting Salinger. I asked her once, but she dismissed the idea, and we haven’t spoken of it much since.

Blair Fuller is an editor emeritus of The Paris Review. He is the author of two novels, A Far Place and Zebina’s Mountain, as well as Art in the Blood: Seven Generations of American Artists in the Fuller Family. He lives in Tomales, California.

No comments:

Post a Comment